Segregation in Sun Valley: A “Working Man’s Paradise” for Whites Only

By Eric Dietlein October 2024

Despite a series of Supreme Court rulings going back as far as 1917, segregationist practices intensified for decades and erected physical barriers, neighborhood by neighborhood, that created a long-enduring legacy of de facto segregation. Ironically, the pattern of segregation is more prevalent in the subdivisions that were built in the 1940’s through the 1960’s, than in most of the antebellum South. The post-war period of suburbanization was a period of resistance to the Reconstruction Era Constitutional amendments which guaranteed equal protection under the law for all. Private housing discrimination was declared illegal by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, exactly a century after the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment. The pattern segregation left still remains on the landscape today and it is fading away only ever so slowly.

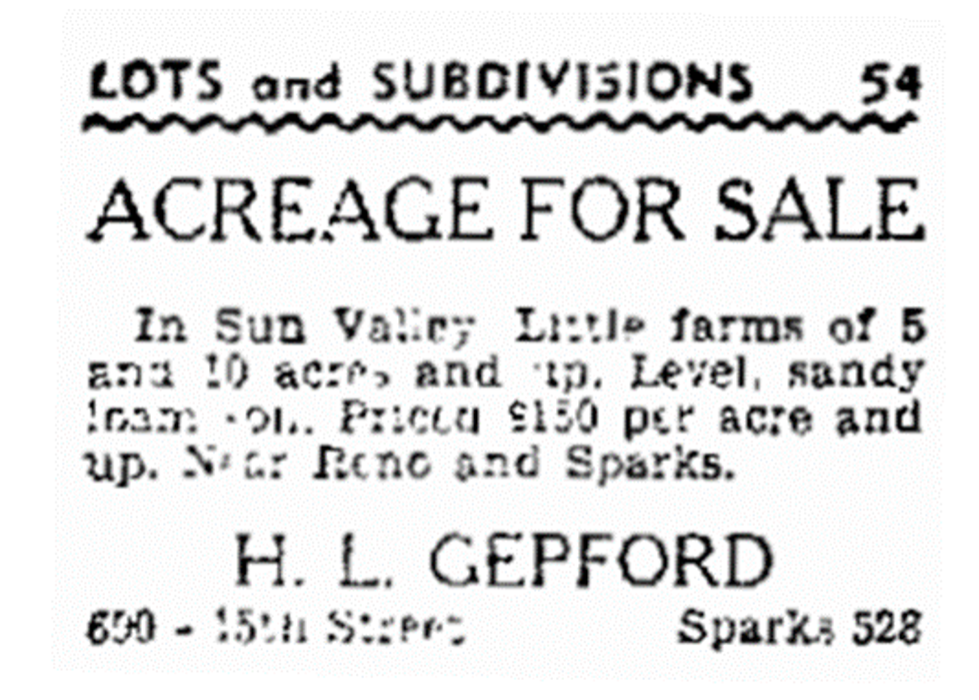

Harry Gepford was a businessman who moved from the farming areas of Central California, to Nevada in 1928. His actions typified how many subdivision land developers shaped patterns of segregation in the Reno area. Most of Geprord’s legacy is buried in recorded documents, like parcel maps of his subdivisions in an area that he would later dub ‘Sun Valley’ and call “a workingman’s paradise.”

Gepford’s workingman’s paradise was a large tract of land he had pieced together through the purchase of individual farming tracts and sheep grazing lands directly North of Reno and Sparks through the 20’s, 30’s and the 1940’s. In and around 1948, Gepford began to subdivide his land into smaller tracts and cut in dirt roads. He began selling tracts of land ranging from one acre to hundreds of acres, and typically financed the sales under his terms as a seller-financer. Gepford included racially restrictive covenants on the deeds to his tracts, in the mold of William Levitt, who refused to drop racially restrictive covenants at any of his huge Levittown subdivisions in the Northeast, because it was a good business practice in his eyes. It makes sense that Gepford also thought restrictive covenants were a good business practice and he figured restrictive covenants would make his lots more attractive to his target buyer; the white working class and the small-time developer.

Federal fair-housing legislation was not enacted until 1968 and Levitt’s policies successfully resisted 1948’s Shelley v. Kraemer until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, two entire decades later. Thus, Harry Gepford, and thousands of other subdivision developers in the U.S. would continue to include race-based restrictive covenants in their deeds into the 1960’s, embedding a pattern of segregation on the whole Post War suburban landscape.