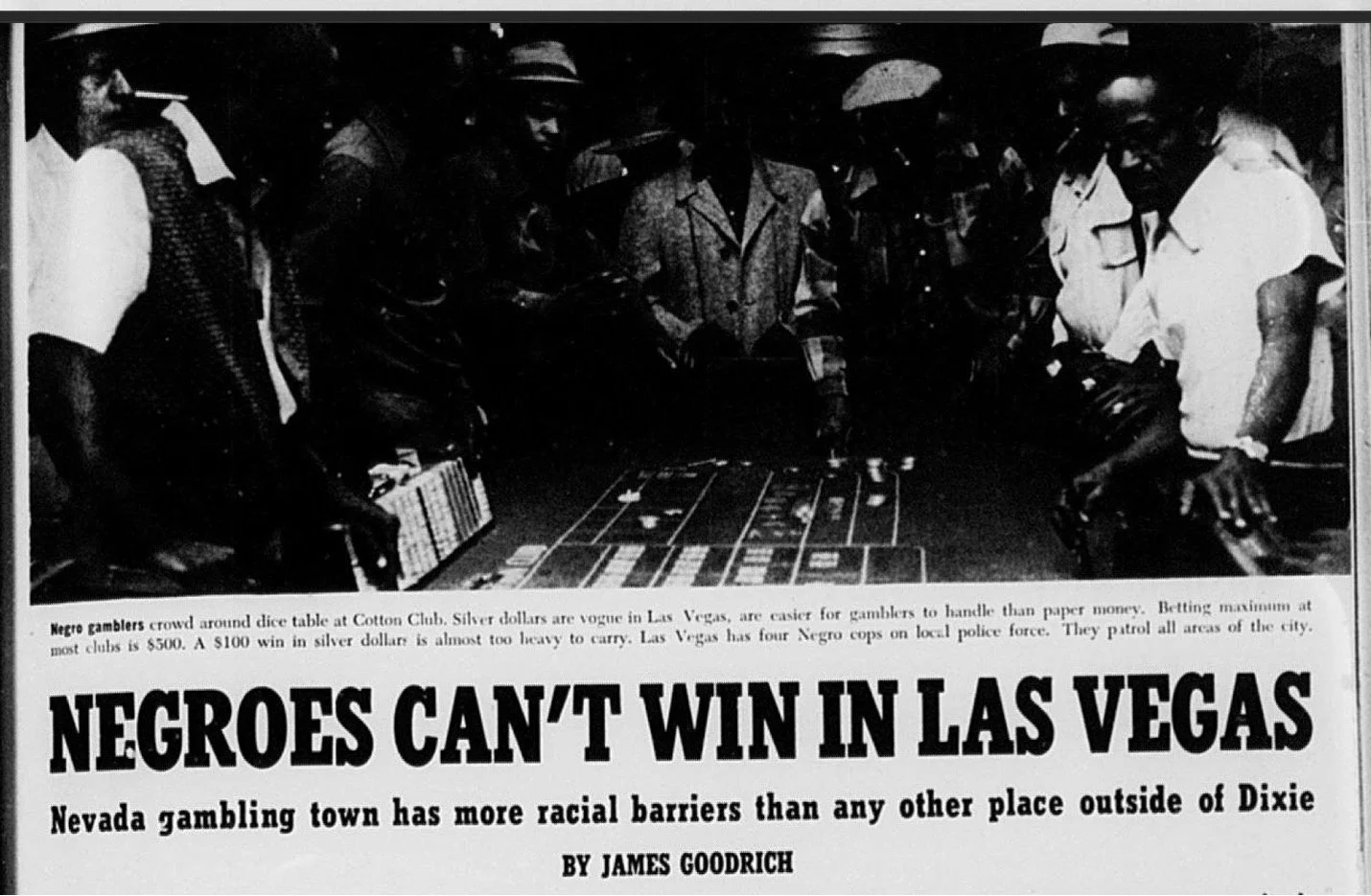

“Negroes Can’t Win in Las Vegas”:

Racial Discrimination in Sin City

By Brandon Kyle

April 8, 2024

During the 1930s, many business owners from the South migrated to Las Vegas to take advantage of its emerging gambling industry, while white organized crime bosses also played central roles in the emerging industry.

Both groups brought racial prejudices with them and helped to establish Jim Crow policies popular in southern states throughout Southern Nevada. These casino giants claimed that efforts to desegregate the Strip or downtown would dissuade Whites from gambling. City leaders, afraid of losing gambling revenues, were complicit in spreading Jim Crow.

In 1954, James Goodrich authored an important article in the Black publication Ebony detailing the conditions of African Americans in Nevada and named it the Western state with the worst civil rights protections for people of color. The inability of Nevada to afford equal opportunity or legal protection to people of color led some African Americans to liken the racial restrictions in Las Vegas to those in the Deep South. Goodrich’s critiques warned African Americans outside of Nevada: Do not come to Las Vegas.

In the opening of his article, Goodrich detailed the extremely unpleasant treatment of African Americans in the Silver State. The existence of Jim Crow in Las Vegas meant that African Americans were only allowed near the Strip or downtown if they were employed there or involved with the entertainment business. However, the job market in Las Vegas heavily favored White applicants; the employment of African Americans on the Strip was minimal and often exclusively related to sanitary, housekeeping, or kitchen positions. It is for this reason that Goodrich remarks that “whenever a Negro is spotted…downtown…,it is safe to wager that he is behind a broom, mop, or dishcloth” with the lowest wage and most degrading task; it was not uncommon for establishments in downtown Las Vegas or the Strip to have a “No Jobs for Negroes” policy.

The public accommodations for people of color in Las Vegas were extremely segregated. For instance, only two restaurants in the downtown area would serve African Americans. If African Americans were lucky enough to find a facility that would welcome their business, they would often have to adhere to strict Jim Crow standards, such as seating themselves in the segregated section of a theater. All but one Vegas casino at the time refused to admit African Americans or allow them to wager bets in their establishments. Only one downtown casino, “Orange Julius,” allowed African Americans to gamble.

To lend credibility to his argument, Goodrich also details the experiences of popular Black entertainers including Herb Jeffries and Lena Horne. While some may assume that their celebrity status would afford them certain privileges in Nevada, the stiff Jim Crow policies in Las Vegas usually extended to popular performers as well. While some performers — depending on their popularity — could stay in the white section of a hotel, they were typically instructed to avoid socializing with white folks on their floor or in the parlor. More often than not, Black celebrities would be denied services located near the location where they were performing.

The housing situation for African Americans in Las Vegas was one of the most pressing concerns for the Black population in Southern Nevada. Due to the segregated conditions of the city, the majority of African Americans were concentrated in “Westside,” a segregated and unmaintained part of Las Vegas that lacked paved roads, reliable lighting, proper plumbing, and running water. Most housing units in Westside — upwards of seventy percent — were neglected and unmaintained. Black families in Las Vegas would crowd into these small units and attempt to share the little space they could afford. Like all ghettos, Las Vegas’ West Side housing was expensive and inadequate for the community’s needs, but prices remained high because racism constricted options for African Americans.

“From where the Negro eyes the world in Las Vegas, two shadows are omnipresent in his perspective—the ‘mean white boss’ and a damnable job,” Goodrich concluded. “He cannot escape either, if he chooses to remain in the town. There is no other course open to him.”